Financial Instruments & Support for Renewable Energy

► Back to Financing & Funding Portal

Overview

Finance is essential for renewable energy technology (RET) projects in two ways[1]:

- Without funds projects would not materialize, and

- With inadequate financing structure and conditions the disadvantage in competitiveness of RET would even increase, as the costs of electric power utilizing renewable energy technologies are highly sensitive to financing terms.

Financial Instruments

There are various types of financing instruments that exist to support the scaling up of renewable energy technologies (RETs). The choice and availability of instruments largely depends on if the project is being undertaken in a developed or developing country, and also on the stage of development of the technologies or projects in question. These can be broadly grouped into those that can be used in addressing financing barriers; those used to address the risks of RET investments; and those that address both simultaneously.[2]

These financial instruments can be distinguished by the level of risk assumed by the the entity funding the instrument concerned, and also by the level of leverage involved. The figure below illustrates this. The financial instruments in the figure are organised on the horizontal axis by their primary focus: whether to address underdeveloped financial markets, the risks and costs of RETs or both. The vertical axis organises the instruments by the level of risk and leverage associated with their use [2]

![Source: The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds. [Online] Available at: https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/cif/sites/climateinvestmentfunds.org/files/SREP_financing_instruments_sk_clean2_FINAL_FOR_PRINTING.pdf](/images/thumb/0/0e/RE_Financial_Instruments.PNG/650px-RE_Financial_Instruments.PNG)

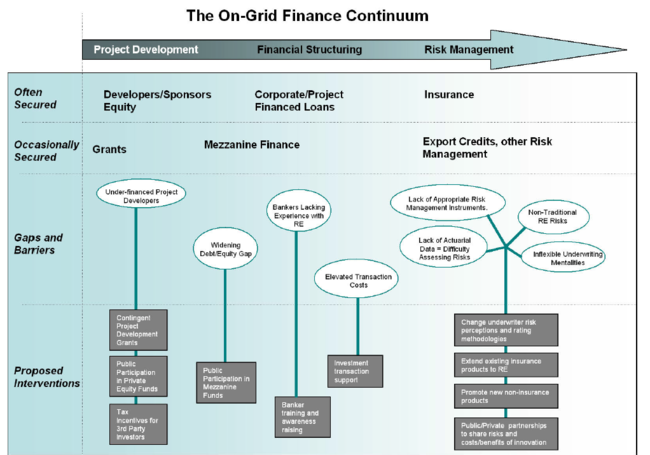

On-Grid Renewable Energy Finance

On-grid renewables projects face the key issue of how to create a price support mechanism that provides stability and predictability over the medium and long term. This can reduce the risk premium in the cost of capital, which in turn can increase the amount of investment in renewables and lower the price that consumers have to pay for RE. For on-grid projects the finance sequence is incomplete, and these gaps can often onl be filled with niche financial products. Some of theses products already exist, while some need to be created. The figure below shows which types of finance are often secured by on-grid projects, which types are occassionaly secured, and the current gaps and barriers in the finance sequence [3].

Various forms of capital are involved in the financial sequence/'continuum' of grid-connected RETs as shown in the figure below. The conventional power sector financial sequence includes these sources of capital:

- Equity Finance

- Debt Finance

- Corporate or Project Finance

- Guarantees

- Insurance[3].

Equity Finance

RE equity investments involve investments by a range of financial investors including Private Equity Funds, Infrastructure Funds and Pension Funds, into companies or directly into projects or portfolios of assets.

Different types of equity investors will engage depending on the type of business, the stage of development of the RET and the risk associated with it (See the table below for more information). For instance:

- Venture Capital is focused on 'early stage' technology companies

- Private Equity firms focus on later stage financing of more mature technologies or projects. They generally expect to exit their investment and make returns in 3-5 year.

- Infrastructure Funds are interested in lower risk infrastrucure such as roads, rail, grid, waste facilities etc, which tend to have a longer term investment horizon and thus expect lower returns over their period.

- Institutional Investors such as Pension Funds have an even longer time horizon and larger amounts of money to invest. They have a lower risk appetite[4].

Funds use Internal Rate of Return (IRR, or ‘rate of return’) of each potential project as a key tool in reaching investment decisions. It is used to measure and compare the profitability of investments. Funds will generally have an expectation of what IRR they need to achieve, known as a hurdle rate. The IRR can be said to be the earnings from an investment, in the form of an annual rate of interest[4].

| Features of Funds Providing Equity | |

| Venture Capital Funds |

|

| Private Equity Funds |

|

| Infrastructure Funds |

|

| Pension Funds |

|

| Source: Adapted from [4] | |

Debt Finance

Debt financing comes in the form of loans and requires the repayment of both the principal sum borrowed and interest charged on that principal. Generally financial institutions will only provide debt finance to projects and project developers once the market is mature and therefore often need encouragement to enter the market. Debt finance can be provided to local finance institutions to allow them to on-lend to consumers, to project developers, or debt can be provided directly to a project developer. The debt must be repaid whatever the outcome of the project[5].

International funds dedicated to development projects such as are provided by Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) will often create loans with generous repayment terms, low interest rates and flexible time-frames, such loans are called "soft-loans"[5].

Investment and commercial banks can lend money against the assets of the project. In the event of defaulting on the loan the bank can have no other claims other than the assets of the project. This type of financing is based on long-term commercial loan contracts[5].

Senior Debt

Senior debt provided from public sources, takes its place among the first creditors to be repaid from a project. It is primarily used to reduce the costs of the project, by providing concessionary funds that may be blended with more expensive commercial funding, and to offer longer-term debt than may be available in local financial markets. Long-term loans from public sources can also help establish credibility among private financiers for longer-term lending to RE projects. A wide variety of debt amortization and repayment schedules can be used, allowing tailoring of debt service costs to project cash flows. For example, a bullet (one-off) repayment of the loan principal may be made at the end of the loan term, reducing debt service costs in the initial years of the project[6].

A distinction can be made between direct loans to project companies and the provision of credit lines extended through commercial financing in- stitutions (CFIs) or other intermediaries. Credit lines can create incentives for intermediaries to extend their own loans to RET projects along- side that funded from the credit line as well as allowing blending of commercial and conces- sionary loans to reduce overall costs. The choice of intermediaries is discussed in chapter[6].

| Senior Debt | ||

| Uses | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds[6] | ||

Subordinated Debt/Mezzanine Finance

This type of lending sits between the top level of senior bank debt and the equity ownership of a project or company. Mezzanine loans take more risk than senior debt because regular repayments of the mezzanine loan are made after those for senior debt, however, the risk is less than equity ownership in the company. Mezzanine loans are usually of shorter duration and more expensive for borrowers, but pays a greater return to the lender (mezzanine debt may be provided by a bank or other financial institution). A RE project can seek mezzanine finance if the amount of bank debt it can access is insufficient: the mezzanine loan may be a cheaper way of replacing some of the additional equity that would be needed in that situation, and therefore can improve the cost of overall finance (and thus the rate of return for owners) [4].

| Subordinated Debt / Mezzanine Finance | ||

| Uses | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds[6] | ||

Project Finance

Project Finance is debt that is borrowed for a specific project. The amount of debt made available is linked to the revenue that the project will generate over a period of time, as this is the means of paying back the debt. This amount is usually adjusted to refelct inherent risks such as the production and sale of power. Should there be a problem with repaying the loan, the banks will establish firts 'charge' or claim over the assets of a business. The first tranche of debt to be repaid from a project is called 'senior debt' and is described in detail below.[4]

Usually, project preparation for on-grid RE projects is carried out by large energy companies or specialised project-development companies. Energy companies finance the project preparation phase from operational budgets. On the other hand, specialised companies finance this phase through private finance, capital markets or with risk capital from venture capitalists, private equity funds, or strategic investors.

Guarantees

Insurance

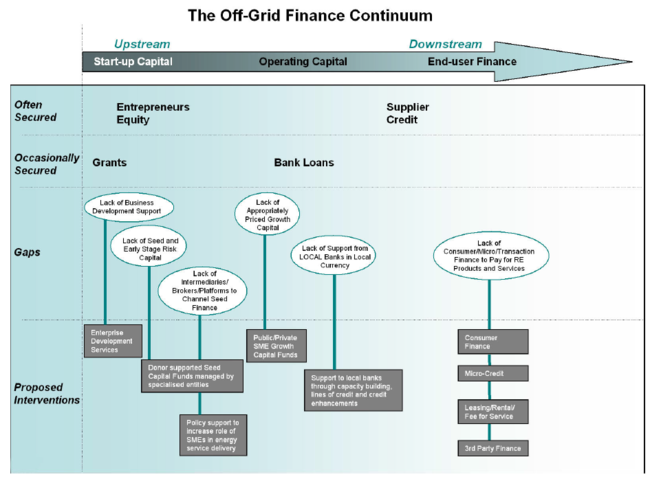

Off-Grid Renewable Energy Finance

Results-Based Finance

► Read about Results-Based Finance here

Microfinance

► Read about Microfinance here

Carbon Finance

► Read about Carbon Finance here

Further Information

References

- ↑ Lindlein, P. & Mostert, W., 2005. Financing Renewable Energies - Instruments, Strategies, Practice Approaches, Frankfurt am Main: KfW.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds. Available at: http://bit.ly/UFHIPy

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sonntag-O’Brien, V., Basel Agency for Sustainable Energy, Usher, E. & UN Environment Programme, 2004. Mobilising Finance for Renewable Energies - Thematic Background Paper, International Conference for Renewable Energies. Bonn, Renewables 2004.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Justice, S., Hamilton, K., Sonntag-O’Brien, V., UNEP Sustainable Energy Finance Initiative., Liebreich, M., Greenwood, C., & Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Private Financing of Renewable Energy - A Guide for Policymakers. 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wade, H. (2005). Financing Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Development in the Pacific Islands.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds.